The Great American Exodus

Perspectives of an immigrant--and a perpetual second-class citizen--on the mass exodus of Americans overseas

This article is my contribution , a publication with thoughtful long-form essays providing analysis, insider perspectives, and no-BS takes on global affairs, economics, and the issues that matter. I find it a great source of information and education that answers many of my pressing questions in these perilous times. Please consider subscribing.

In late 2023, writer Kristen Powers published an article titled “The way we live in the United States is not normal.” It went viral and inspired countless Americans to dream about or start making plans of moving overseas—particularly Europe. The author and her spouse have since moved to Italy.

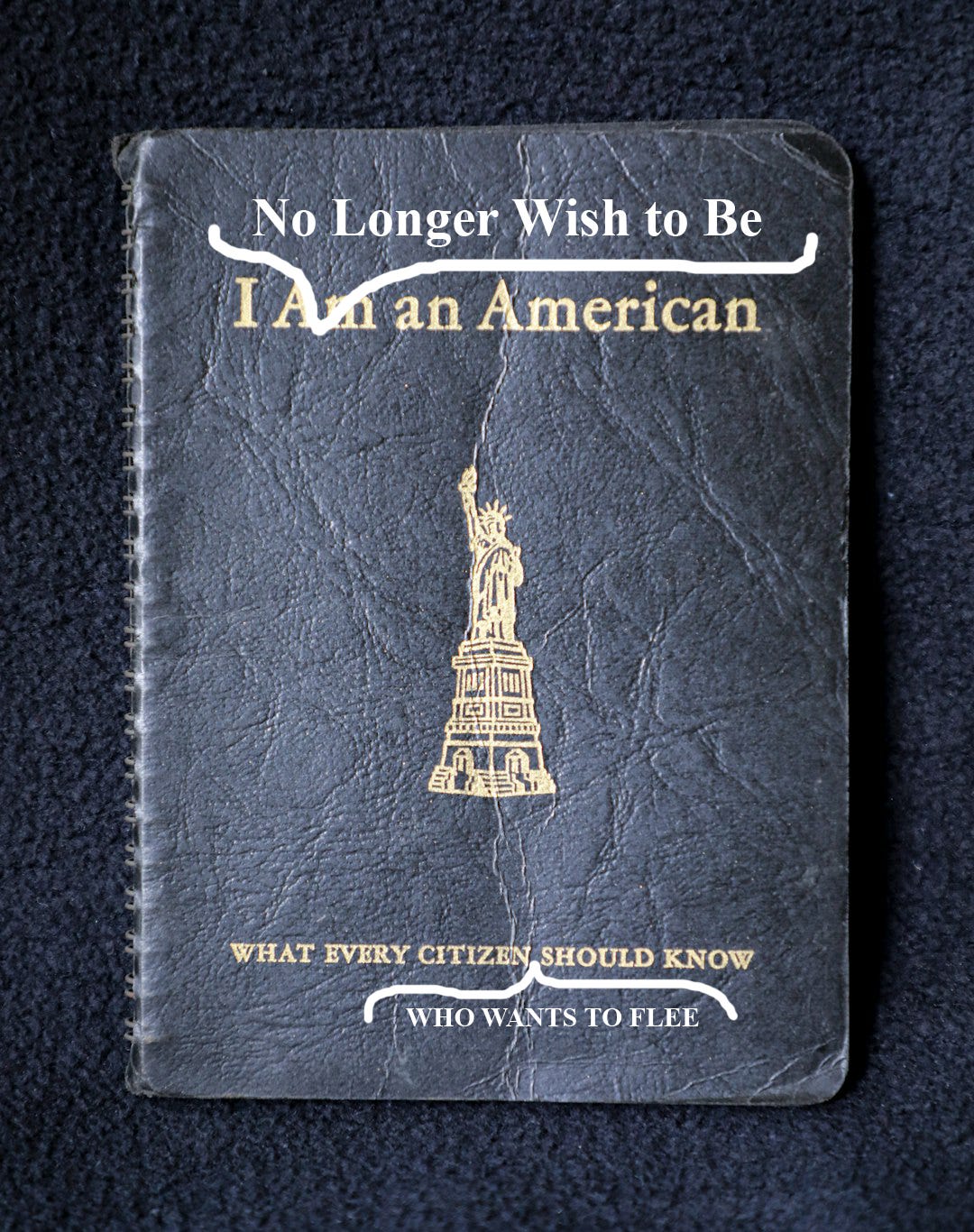

Over the past few years, moving abroad became a cool trend that turned into the “Great American Exodus.” Social media influencers turned it into a giant lollipop for those of us who were stuck in the States to drool after. Of course, it tasted more like sour grapes.

Fast forward to the Time of Trump 2.0, the desire of Americans wishing to move abroad has increased. The Great American Exodus trend accelerated after the November 2024 Election.

Some of the push factors behind this exodus are:

Social and political unrest

Fear for personal safety

Rising living costs and stagnant wages

Unaffordable and inaccessible healthcare

Unaffordable retirement

Lack of a sense of community

With the current administration’s destruction of the law of the land and the very fabric of the American society itself, there is a rising sentiment of panic about the imminent future of this country. Like a “blind fly fumbling around” (a Cantonese idiom), folks are looking for a country to move to.1 Many don’t care which country—just any country that would take them. They have no idea how to go about doing it.

A frequently asked question on Google search is: “What countries are Americans fleeing to?” “Where to go to get out?”

Some of the most popular choices2 include:

Mexico

Canada

UK

Germany

Australia

Israel

South Korea

France

Japan

Italy

In addition, the following countries have been mentioned a lot by American expats on social media:

Portugal

Spain

Greece

Caribbean nations

Costa Rica

Colombia

Ecuador

Thailand

Malaysia

Dubai

Whether you’ve already made the move, have been planning a move, or are fearful of your future and looking for a way to get out fast, leaving the country where you’ve lived your whole life is not a piece of cake.

I’m not an expert who can give you any sort of practical advice about how to secure a second passport and how to handle all the logistics of moving overseas. However, as a serial immigrant my whole life, and having lived as a second-class citizen in Western countries, I want to share some insights from my personal experience. I hope my perspectives can help you make informed decisions regarding whether or not you want to live as a foreigner the rest of your life—especially given the current international hostility toward the United States and a less-welcoming attitude toward Americans.

The TikTok Videos That Made Me Cringe

Let me go back to that viral article I mentioned in the beginning.

At the time this article was published, I’d had many heated conversations with my ex-partner, who was hell bent on moving overseas. Like the author of the article Kirsten, my ex had been pointing out all the things in the States that were “not normal.” Every day, he would forward me TikTok videos showing “expat life in a paradise,” sent from countries like Thailand, Vietnam, and other exotic places. In these paradises, everything was cheaper and much better quality than what you’d find in the States, especially healthcare.

I was bombarded with huge doses of anti-American and how-everything-is-better-overseas sentiments. They constituted my ex’s campaign to convince me that moving overseas would be a great choice. Little did I know that I had little say about the choice, and that the country he unilaterally decided to move to was the same country he visited multiple times alone, where he actively cheated on me while campaigning to move there. Anyway, the TikTok videos made me aware of the American Exodus trend, which were already in full swing.

I remember reading an article in The New York Times from 2023 about American expats living the “Good Life on the Cheap” in Europe. It sheds light on how the arrival of Americans had driven up housing costs for the locals and made life difficult for them. Some European cities and towns such as Lisbon also became Disneyfied to cater for American expats and tourists.

When I heard the stories of Americans—mostly young ones in their 20s and 30s—touting the horns of how they could sort of “have it all” in Europe, I couldn’t help but cringe. Yes, I admit I did feel a bit envious. But I did not have the option to move (having to stand by and care for my elderly mom in the States). Plus, I was burnt out from moving from continent to continent so many times in my life that I was really hoping to put my roots down.

The reason I cringed was because I saw this trend as a kind of neo-colonialism.

Before I delve into what I mean by neo-colonialism, let me give you a brief intro to my life as a colonized second-class citizen for context.

My Journey as a Second-Class Citizen

At the age of 4, my family and I moved from authoritarian China to Hong Kong, a British colony. The two vastly different worlds were separated by a river and an immigration checkpoint with barbed wires and Gurkha soldiers on guard.

Although we shared the same Chinese ancestry and many common traditions with the locals, we the “Mainlanders” were looked down upon by the locally born and raised “Hong Kongers.” Speaking the local dialect Cantonese with an accent would automatically reveal your background as a political refugee—considered a second class citizen. Even in my young mind, I picked that up rather quickly, seeing how my mother with her thick accent was given prejudiced treatment in stores and other public spaces. I immediately understood that to be accepted fully and to belong to our new hometown, one had to speak the local language without an accent. Given our tender ages, I and my brother picked up Cantonese easily. But the next big hurdle was English.

The British colonizers had created a hierarchical society where the Brits and other white folks belonged to the upper strata. They didn’t mix with the locals, except for the upper and professional class of Hong Kongers. The later would speak English fluently. So money and English were the tickets to privileges.

My family didn’t have money, nor were we able to speak English fluently. In fact, I was humiliated by my upper-class schoolmates because my English was subpar. From then on, I decided that I would master English to such a degree that no one—not even the upper-class kids—could laugh at me and call me “stupid” again. I made it, but only in the context of our tiny colony of 5 million. Even so, due to our immigrant background and poverty, our life experience was very limited. The expensive venues and activities were off limits to us.

When I moved to the United States, I was made to feel stupid again because of my English. The type of English I spoke was school-book British English. I couldn’t understand spoken American slang and had to start from scratch to adapt and blend in. Well, this is just one of the many obstacles I faced as an immigrant to a new country. But I accepted the challenges and didn’t expect a smooth path. I knew I was in a disadvantaged position but I believed in social mobility, so I worked double as hard only to be given opportunities that were half as good as the locals.3 Still, I counted myself lucky because, after all, I could speak English. My parents, who could barely speak the language, had to work on low-wage jobs where they worked themselves to the bones.

The language barrier has forced many first-generation immigrants to accept jobs that they over-qualify for. Engineers working as taxi drivers. Physicians working as housekeepers. Teachers working as toilet cleaners. To the average American, they are cheap labor. But to immigrants, we know we are under-appreciated talents with dignity—as a Chinese saying goes: “heroes who have no place to show their kung fu.”

When I moved to Sweden after marrying a Swede, I faced a subtle, unspoken kind of discrimination (e.g. employees avoided picking candidates whose names didn’t sound Swedish), as well as setbacks in my career and earning abilities. I did learn the language quickly but wasn’t able to use it in my professional capacity, and that limited my options. I also observed an under-the-surface resentement toward immigrants, based on the belief that we were taking their jobs.

One thing I was so accustomed to that I almost forgot to mention, is the constant bureaucratic hassle of applying for visas, residency permits (e.g. Green Card) and citizenship. Every year for seven years in Hong Kong, my family had to wait outdoors in long lines to renew our residency papers. Then, it took 10 years and a big part of my parents’ savings to secure our Green Cards, followed by our citizenship.

Immigrant vs. Expat

No matter where I moved, I was an “immigrant,” which means I was (and still am) a second-class citizen.

By contrast, Americans living abroad are considered “expats.” The term carries with it a sense of privilege, and signals having the option of moving back home (or “repatriate”).

Because of its historically favorable international image since WWII, America and its people are generally welcome everywhere they traveled. The Mighty Dollar also became an unspoken leverage for Americans when they traveled, and locals would smile and cater to their needs in order to earn their dollars so they could live a better life.

I saw this with my own eyes when I traveled to Chiang Mai, Thailand—a city that caters to Americans and Europeans. I don’t doubt the genuine friendliness of the locals, but I’ve also understood that many were simply tolerating the entitled and arrogant behaviors of Americans because they needed the money that Americans—and to some degree, Europeans—brought in.

Fellow writer Elizabeth Tai has made a similar observation about the influx of foreigners into her country, Malaysia. I resonate with many of the eloquently expressed sentiments in her article, “American friends, you can’t love your country only when its strong.”

Elizabeth and I share the same view that many Americans brag to their friends and family back home about how cheap [a certain Asian country] is, without realizing that they come off as privileged colonizers through the way they conduct themselves. They also don’t seem to be aware that their enjoyment is built on the cheap labor of those who are born into countries that are economically and geopolitically disadvantaged compared with the U.S. For example, when my ex raved about how cheap massages were in Thailand, and kept going back (sometimes three times a day), I asked him if he felt bad about taking advantage of the cheap labor. His answer: “Why wouldn’t you want to take advantage?” I told him how uneasy I felt, having lived under colonial rule and seen the dynamics of how white colonizers exploited cheap local labor. He didn’t seem to be able to understand what I meant. In fact, he dreamed of having servants at home, much the same way colonizers enjoyed cheap domestic servants.

That’s why I call Americans looking to live “life on the cheap” overseas “neo-colonialists.”

In response to my comment, Elizabeth writes, “it's very difficult to put into words the feelings I go through when I see people using geo arbitrage to get a more luxurious life in my country. Like, somehow, they're using us in some way.”

Having lived as a colonized citizen, I totally get it. But most people don’t. Elizabeth has been accused to be “too sensitive” for having felt exploited. I would urge Americans living on someone else’s land to stop questioning or gaslighting the locals for the feelings they hold toward their own home.

Advice from Fellow American Emigrés & Travelers

Although many American expats are unaware of their entitled ways when they travel and live abroad, I’ve also come across some who are well aware of their privilege and choose to be mindful about it. Below is my curation of Substack writers and their essays dealing with the subject of emigration.

1️⃣

lives in his chosen countries with an attitude of humility and respect for his fellow citizens. He writes about expat life in Europe and helps his readers conduct a reality check on whether they are actually capable of living in Europe in this article, “Are You One of the Few Americans Who Really Could Move to Europe?” (Highly recommended.)The overaching advice to his readers, to which I wholeheartedly agree, is this:

Be grateful if you’re allowed to live in a foreign country that would take you.

Be grateful if you enjoy a certain status that “immigrants” don’t (“immigrants” in the way that’s typically perceived in the U.S., i.e. second-class citizens).

2️⃣One of my favorite writers on Substack,

, has recently published a series of articles detailing what to consider and look out for if you want to move overseas. She has traveled around the world and done a ton of research on specific countries. Not only is she doing hard-core recon before making any decisions of moving abroad, she also shares clear-eyed advice—along with many interesting stories—with her readers so they know what they are getting themselves into should they take the plunge.Thinking of Moving Overseas? We're Too Old to Make Big Mistakes

Making the Move Out of America: An Object Lesson on How NOT To Do It

You're Too Old to be This Foolish: An Expat Gets Injured Over a Thirty-Cent Bus Fare

I want to highlight this advice from the last story in particular:

“Having greater empathy, especially in the Time of Trump, will go a long way towards better ensuring our safety.

We expect immigrants to be respectful of our laws and understand how they are perceived here, fairly or unfairly. Same goes for us.

Respect and good will are earned. Let’s earn them.”

3️⃣According observations by Michael Jensen and Brent Hartinger, who have been traveling around the world as nomads over the past eight years, anti-American sentiments are growing globally as Trump doubles down on his isolationist foreign policy that alienated U.S. allies.

Already, American tourists are encountering more hostility and less friendly treatment than before due to an erosion of trust in our government. Brent and Michael observe that some Americans abroad even tried to pass as friendly Canadians to avoid hostility. Here’s the response (on Facebook) of a Canadian upon hearing this tactic: “If you want to become Canadian, there are several pathways to do so, and you will be welcomed with open arms. Until then, please don’t hijack our global reputation because your country embarrasses you.”

4️⃣Mindful migrant, an American immigrant in Portugal, has shared with me her experience of moving there, and the conflicting emotions she holds about leaving the States for a better future for her daughter:

5️⃣Of course, I can’t write a story about Americans living abroad without mentioning my long-time friend, soul bestie and fellow writer Amy Brown. She has recently moved to Spain from the U.S. to be closer to her two daughters, both of whom live in Europe. I’ve known Amy since the days we lived in Sweden, about 25 years ago. Amy is an “old hand” when it comes to migration. She is one of those Americans who exercise the utmost respect to the local people and does her best to adapt to the local cultures wherever she lives. If you’re looking to move to Europe, I highly recommend connecting with her through her Substack, Living in 3D. I must admit that when Amy decided to make the trans-Atlantic move, a wave of sadness swept over me, reminding me of the time when my high school classmates left in droves with their families to settle overseas during the grand exodus of Hong Kongers prior to 1997 (in anticipation for gloom and doom after the handover of the British colony to China).

My Own Advice

Americans, by virtue of the dominance of their language and Dollar around the world, as well as their powerful passport, have traditionally never had to consider mastering foreign languages and begging for visas. Hence, no need to worry about being a second-class citizen when abroad. But things are a-changin’.

To prepare you for a vastly different future where Americans will not be readily welcomed around the world, here are some words of advice from my lived experience as a serial immigrant and perpetual second-class citizen:

If you decide you’re going to live the rest of your life in a foreign country, consider yourself an immigrant instead of a privileged “expat.” Or, try the term “emigré” if you want it to sound fancier! Let me repeat what Gregory Garretson said, “Be grateful that you’re allowed into another country.”

Don’t assume that if you move to a European country, the culture there would be similar and easy to adapt to. For example, Swedish people value a concept called “jantelagen”—unspoken rules that discourage people from thinking themselves as better than others. A thumb that sticks out will be pushed down. They also live by the philosophy of “lagom” (just enough). They abhor excess and bragging. The American style of individualism and “the bigger, the better” doesn’t sit well there. If you can’t stand that, it would be very hard to live happily in that society.

Don’t tell people what they should do just because their way of doing things is different from what you’re used to in America. Julia Hubbel tells a story in one of her articles cited above, of an American woman who couldn’t stand the sight of laundry hanging on lines outside buildings. She told the people to stop doing that! Can you guess the reactions of the locals?

No matter where you live, study the local langauge, be curious, and learn from the locals how things are done and what they value. Even if you are irritated by the bureaucracy of becoming a resident, just follow the damn rules.

Lastly, I’d like to quote

, integrative physician, on her note posted on February 20, because I can’t say it better:If you live in the US and it is the first time you are feeling this scared and unsafe because of the present administration, consider that it is not the first time it’s scary, but instead the first time for you, because of your privilege.

Marginalized communities have had a long history of feeling unsafe and threatened. The difference is now systems are dismantling to a degree that affects more people.

You don’t need to feel defensive, guilty, or bad about your privilege…we all have relative levels of privilege of race, socioeconomics, gender identity, etc. Instead use this a critical moment to…

❣️Build empathy for other communities and oppression

💡Realize we are all more connected and vulnerable than you knew.

✊🏽Understand that we all rise if we all rise and we all fall when we all fall. Fighting for Justice matters, even if the reason to fight doesn’t directly impact you.

None of this necessarily makes the current situation easier to bear. But it could help us come together as a stronger collective.

Bonus:

I want to wrap up this article with a video showing the treacherous journeys of Chinese migrants who tried to enter the United States through its southern border. This reportage dispells the misconception that assylum seekers are all criminals and greedy folks who just want to partake from the “pot of gold” in America. One of the families interviewed in the video shared the reason why they trekked all the way from China, through Thailand and Turkey, to Colombia on their way to America—religious freedom, especially for their daughter. When the father expressed his desire to “have a taste of freedom,” he teared up, and so did I. His desire reminded me of the same from my parents. It was the dream to express themselves freely that drove them to leave China and move to America in the first place.

I believe it’s important for Americans to hear stories like this to understand why foreigners droppped everything and even risked their lives to enter the country. Well, perhaps one side effect of this current Great American Exodus is an increased understanding of what it means to be a political assylum seeker (or, refugee), and how it feels to be a “second-class citizen.”

Check out this discussion thread on

’s Substack chat (scroll to the very top and keep loading more to reveal the question: “To what country can my family and I flee??? We are dead serious about leaving the US and giving up our citizenship. This country is a disgrace and completely unsafe.”Statistics about Americans abroad (Feb 2025): https://blog.savvynomad.io/statistics-americans-abroad/

World Population Review: American Expats by Country 2024: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/american-expats-by-country

It is an unspoken rule that we immigrants have to work many times harder to have a chance to be considered equal in our host country. See the story of “Ten Times Better” featuring pioneering Chinese American ballet dancer George Lee.

The idea that people make such harrowing journeys to the US to taste freedom and now find that this freedom is crumbling to nothing, is so devastating. As critical as I’ve always been here, now I’m wondering how school teachers are handling the teaching of American history, a govt of checks and balances, of our nation of immigrants? The waves of grief that this is happening. That the years, a lifetime, of fighting to prevent it are washing away with all this dismantling. It’s too much. I feel so deeply embarrassed. I’ve protested with a handmade sign that reads, The Whole World is Watching. It cuts in so many ways.

Hi Lily,

Very insightful post! Before I say anything else, I should mention that I’m not American—I’m from Slovenia.

I recently came across the term ‘geo-arbitrage’ in a post by a Canadian who, along with her husband, retired at 33. She wrote about how they maximize their investments by living in lower-cost locations. She even mentioned wanting to further increase their income from financial investments so they could afford to travel with hired help to care for their small children and stay in more upscale Airbnbs.

I do think it’s important to discuss the issue of cheap labor in these contexts. Having lived and worked as an expat in Ethiopia for ten years—first in a low-paying academic job and later in a much higher-paying international development role—I also hired household help. I made an effort to pay them above the local rates (while still finding it very affordable) and to treat them with dignity and respect, including offering paid leave and fair working conditions.

One thing I learned in Ethiopia—and before that in Burkina Faso—is that hiring help is not exclusive to expats. Anyone who can afford it does so. My cleaning lady, for example, had a maid of her own, whom she paid so little that it broke my heart. The same was true for many of my Ethiopian colleagues and friends. In fact, the treatment of domestic workers by local employers was often quite harsh.

This isn’t to excuse expats’ reliance on cheap labor, but based on my nearly 20 years of work and travel across Africa, I’ve observed that many locals actively prefer working for expats because the pay and conditions tend to be better. I also want to add that, being a social anthropologist, during my time in Ethiopia and Burkina Faso, I made the effort to learn the local language and understand social norms. I believe that integrating into the culture and respecting local ways of life is essential when living in another country.

At the same time, it’s just as important to maintain a critical perspective. Local customs, including labor practices, are shaped by complex histories and power dynamics, and they don’t always align with principles of fairness or dignity. Respect for culture should go hand in hand with thoughtful reflection and, where possible, a commitment to ethical engagement.

On a different note, during my 2.5 years in Stockholm, I also saw the opposite of ‘lagom’ or ‘jantelagen’. While Sweden is often associated with modesty and balance, I witnessed excessive consumption, people flaunting their wealth, and even young people pouring champagne down the drain just because they could. I even saw people wearing ‘Fuck Jante’ T-shirts, openly rejecting the cultural norm of humility. It was a stark contrast to the image of Swedish restraint that many outsiders hold.