English as America's Official Language: An Executive Order that Reeks of Linguistic Imperialism

The threat of normalizing discrimination against people who have limited English-speaking skills, and why it's ever more important to decolonize our view of English.

Among the dizzying flurry of Executive Orders signed by Not-My-President Donald Trump, there is one that triggered and infuriated me the most: Making English the official language of the United States.1 Did you miss it?

If you are a native English speaker, this may be a piece of news that pales in comparison with all the other grave infringements of our civil rights by the current Trump-Musk-Vance-Republican regime. But for those of us with an immigrant background, this is a big deal.

While the designation of one or multiple official languages is a common practice throughout the world, and the practice has also been adopted by 30 states in the U.S., the federal government has never designated an official language in the nation’s nearly 250-year history.

Why now? The simple answer is: Discrimination against immigrants. This is completely in line with the stance of the current administration, whose hatred toward immigrants is clearly reflected in its mass deportation policy—no surprise there.

On paper, adopting English as the official language may sound like a good thing. No big deal. After all, everyone speaks English anyway. However, in practice, this Executive Order (E.O.) threatens the necessary life line and safety net that immigrants have been counting on to navigate life in their adopted country.

How so? By rescinding a federal mandate issued by Former President Bill Clinton that required agencies and recipients of federal funding to provide extensive language assistance to non-English speakers. Trump’s order lets agency heads decide whether to keep offering documents and services in other languages.2 The White House took the lead by deleting the Spanish language version of its website. What’s next?

And when language assistance is made optional, guess what is going to happen next?

Why this Executive Order Could Cost Lives

Just to give you a glimpse of what language assistance means in real life, I’m going to share a few examples from the two-year period when I worked as a Cantonese-English interpreter. It was at the height of the pandemic. I was placed on calls with government agencies that oversaw the welfare of seniors living in poverty or with mental illness; ones that handled paratransport for disabled individuals; the Department of Labor, which handled a skyrocketting number of unemployment claims; Child Protection Services and police officers, who investigated domestic violence cases.

More than half of the calls I filed came from doctors from around the country and even Canada and the UK. They needed help communicating vital information to their patients with limited English-speaking ability. These were patients at the Emergency Room due to COVID and other health issues, patients on the operating table just prior to receiving surgery, and family members of patients who were on life support or were about to die.

Those who needed language support also included parents caring for children with learning disabilities. Distressed and desolate seniors who did not get their government-subsidized free meals delivered to their doors in time and were starving. People at the brink of suicide. There was even a case where a patient almost got killed by mistake when his doctor mixed up his name with that of another Chinese patient, who was scheduled to receive Medical Assitance in Dying (Canada).

So, you see, language assistance is a vital service to underserved communities. This is a free service at the cost of the institutions who hire contractors who in turn hire bilingual or multi-lingual immigrants like me to do the job.

💡How many languages other than English are spoken in the U.S?

According to the last available federal statistics, there are at least 350 languages spoken in the United States, with the highest concentration in Queens County, New York (where my family settled three decades ago). But this statistics is no longer available on the original official webpage. It has been replaced by a simple sentence stating that English is the official language of the U.S. per the Executive Order of March 1, 2025.

💡How many people in the U.S. have limited English-speaking ability?

The U.S. Census Bureau’s data3 show that nearly 68 million people, or 20 percent of the population, speak a language other than English at home. The most commonly spoken languages spoken include Spanish, Chinese, Tagalog, Vietnamese and Arabic. In addition, 8.4 percent of people living in the country report speaking English “less than ‘very well.’”

How Language Can Be Used as a Weapon by Colonizers

I am a polyglot. The languages I speak are (in the order that I learned them): Hangzhouese, Mandarin, Cantonese, English, French and Swedish.

I mentioned this not to show off, but to explain how my migration experience forced me to lean on foreign language learning as a survival skill to adapt and acculturate to the countries I moved to. (Well, I never moved to France or a French-speaking country, but I learned it as a teenager to prepare for university studies in Paris—a plan that was shot down by my parents.)

I grew up in Hong Kong, a former British colony. The adoption of the colonizer’s language was the reality I grew up in. I took it for granted. But I also became aware of how language was used as a weapon to wield control and dominance over an entire population.

We, the colonized folks, were forced to deprioritize our mother tongues and focus on the colonizer’s language instead. Being able to speak British English, in my case, was the ticket to higher social status and economic advancement. I don’t carry any resentment toward the English language itself because I seem to have a knack for languages and love the learning process. But many of my fellow students hated it, as they struggled with getting good grades in school, where all subjects except for Chinese were taught in English in the colonial days. Still, I always carry with me the acute awareness of the implicit power dynamics behind language usage.

This is why I see the covert message behind the E.O. as: You immigrants who don’t speak English fluently deserve less rights than those born in the U.S. who are also native English speakers.

When colonizers impose their language on the native people of the land they colonize, it is called linguistic imperialism.

One of the consequences of this practice is that English-speaking white folks who travel or live abroad are generously forgiven if they don’t learn to speak the local language. And if they do manage to pick up a few local words, they are given a standing ovation. Well, not quite, but I hope you get the point. I saw this happen over and over when my ex-husband, a European, flaunted to waiters or shopkeepers the few Cantonese he learned from me while living in Hong Kong. His motivation was simply to elicit a friendly giggle or a look of approval. In all of the 10 years we lived there, he never learned more than 10 words of Cantonese. But he didn’t feel that he needed to. All the locals catered to him by speaking English.

By contrast, when the people of the Global Majority (known as the minorities or marginalized black and brown people) settle in the U.S., their own mother tongues become a liability.

I believe the E.O. is a reinforcement of the anti-immigrant sentiments hidden under linguistic chauvinism.

Austin Kocher, a fellow Substack writer and a scholar who researches immigration in the U.S., explains what linguistic chauvinism means in his essay “Speaking of Nationalism: New Policy Makes English the Official Language of the US”:

"linguistic chauvinism,” […] the belief that certain languages and dialects are superior to others, […] linguistic chauvinism has been weaponized by nationalist movements over the past century both abroad and at home in the United States.

— Austin Kocher, immigration research scholar

Kocher fears that this E.O. may be abused by everyday Americans as a “permission structure to police non-English language use.”

I very much fear the same. In fact, this reminds me of an incident I had in Wisconsin, about 30 years ago. I and a group of my fellow students from Hong Kong were speaking Cantonese on our college campus. Suddenly, someone barged into our circle and interrupted our conversation, shouting loudly: “Speak English!” We froze and didn’t know what to make of this racist “command”!

Non-profit immigrant advocacy group United We Dream issued a press release on their webiste to warn people of the potential consequence of the E.O.:

“Trump will try to use this executive order as a crutch to attack schools providing curriculum to immigrant students in other languages, gut programs and roles that help to promote inclusive language access, and embolden immigration agents to single out and harass individuals who speak a certain way.”

— Anabel Mendoza, Communications Director of United We Dream

Discrimination Against Limited English Speakers

In every country, I have seen immigrants struggle with learning the language of their adopted home. Each country has its own attitude and policy toward their predominant language(s) and other spoken languages. Some are more helpful than others in providing language learning services to newcomers so they can adapt to their new life easier.

In my experience, I found Sweden to be the most generous among the countries I’ve lived in, in terms of providing immigrants the necessary foundation to settle into the society. The government provides free Swedish language classes to every newcomer, regardless of their fiancial status. Better still, since higher education is free to all residents, I was able to enroll in university-level Swedish to bring my language skills to a higher level than the most basic.

In America, all immigrants are left to their own devices to learn English using their own money and time. Some folks might criticize immigrants for being too “lazy” to learn English and therefore not participating in mainstream society. However, little do they know the high cost of learning English as an immigrant.

Once a Foreigner, Always a Foreigner

The struggle and frustration doesn’t just affect immigrants with limited English-speaking skills, who, by the way, are often regarded as “illiterate” by some Americans.

It also extends to immigrants who have spent most of their lives studying and honing their English skills so that they can be fully accepted and integrated into society. Our foreign accent and less-than-100%-perfect English are often used against us in employment situations, for example.

Because limitation in English isn’t among the attributes protected under the various federal anti-discrimination laws (which are being seriously undermined by the current administration), there is no legal recourse if you suspect that you have been passed over for a job on that ground.

Of course, many attributes are factored into a hiring decision. But in my experience of finding work here in the U.S. after having spent 15 years abroad, I can say that language proficiency was definitely a strong consideration. Granted, I have chosen a profession that requires an extremely high level of English proficiency. But I am confident that my proficiency is comparable to native speakers’. Unfortunately, having worked as a writer and editor (almost exclusively in English) overseas didn’t seem to count. Rather, my overseas experience drew a blank among employers and was interpreted as an “employment gap.” It didn’t help that I wasn’t considered an American expat who had repatriated. No. Because I wasn’t born here and have an accent, I would always be a foreigner in their eyes. My ability to do a good job as an editor was not to be trusted because, where on earth is Hong Kong? Sweden? Do they even speak English there?

To survive, for six years I took on minimum wage jobs, working at the front desk of a YMCA in an immigrant community, interpretating—for free—for the manager what the Chinese senior members said. I worked at backbreaking jobs such as a grocery store assistant and a background actor. I also worked as an interpreter, offering my skills in three languages for a wage close to the minimum wage, for a maxium of 25 hours a week (which was set up to prevent us from qualifying for health benefits). It was an extremely stressful job that involved filing dozens of calls per hour with a 15-second break in between—hardly enough to take a deep breath and restore my blood pressure level. Some of those calls were so frustrating that my cortisol kept shooting up the whole day.

Yes, I felt exploited for simply being a foreigner who speaks more than just English! Yet I had considered myself “lucky” to have found any job at all.

‘Punishment’ for Polyglot Immigrants

Recently I had an exchange on Notes with a writer who recounted an experience that her polyglot Dutch husband made upon moving to the States:

The sarcastic conclusion from her husband: “I assume such folks resent that immigrants can usually speak multiple languages.”

Here’s my reply:

The Mental Health Toll of Code-Switching

Far from being “lazy,” immigrants and people of color born in the U.S. often find themselves diligently doing the mental gymnastics of switching between languages, dialects or/and cultural practices.

This is known as code-switching. According to an article on PsychCentral, “code-switching […] happens when someone who is bilingual or bi-dialectal uses their first language or dialect with family and friends, but switches to using Standard English (SE) when speaking to those outside of their communities or in settings like at school or work.”

The same article points out different types of mental and emotional toll that code-switching can lead to, such as overwhelm, burnout, and exhaustion.

In addition to constantly switching back and forth between different languages in my head, I’ve also had a life-long responsibility to help my parents translate from their language to the dominant one where we live. It has been exhausting at times and certainly a huge test of my patience.

I will venture to say that such things have hardly ever been considered by native English speakers. That’s why I feel that the discrimination against people who speak with a foreign accent is unjust.

Christina Ng, a Singaporean, elaborates the extreme challenges of perfecting her English and Chinese skills in her essay, “Tending to My Imperfectly Perfect English(es).” Both are Singapore’s official languages, but her parents speak a combination of three different Chinese dialects, adding complexity to her linguistic identification and learning experience. I resonate deeply with her experience, since my parents used to speak a combination of three dialects at home, while I had to learn both Cantonese and English at school because those were the official languages in Hong Kong. In fact, we have a saying in Chinese—“half a pail of water” (半桶水)—that describes the state of neither here nor there.

The frustration that Ng describes in her essay hit me hard:

…as someone working in English, I needed to prove a lot more about my level of competency when it came to securing a job teaching English.

My greatest fear is that this E.O. will be used by companies to justify prejudiced hiring practices based on a person’s English language proficiency—even if it isn’t a critical requirement of the job. This will further push new immigrants out of the job market, making them even more vulnerable to the impacts of poverty.

Questions to Ponder:

For those of you whose first language isn’t English:

What language(s) do you speak?

Have you ever experienced linguistic imperialism or linguistic chauvinism?

For those of you who are native English speakers, and who have never had to learn another language for survival:

Have you thought about the invisible linguistic challenges that we immigrants go through every single day?

How has this article changed or challenged your perspective on people who speak English with an accent or have limited skills in understanding and speaking English?

Is there something you could do to help?

From the archive

In this essay, I write about my first public humiliation with my first foreign language, Cantonese:

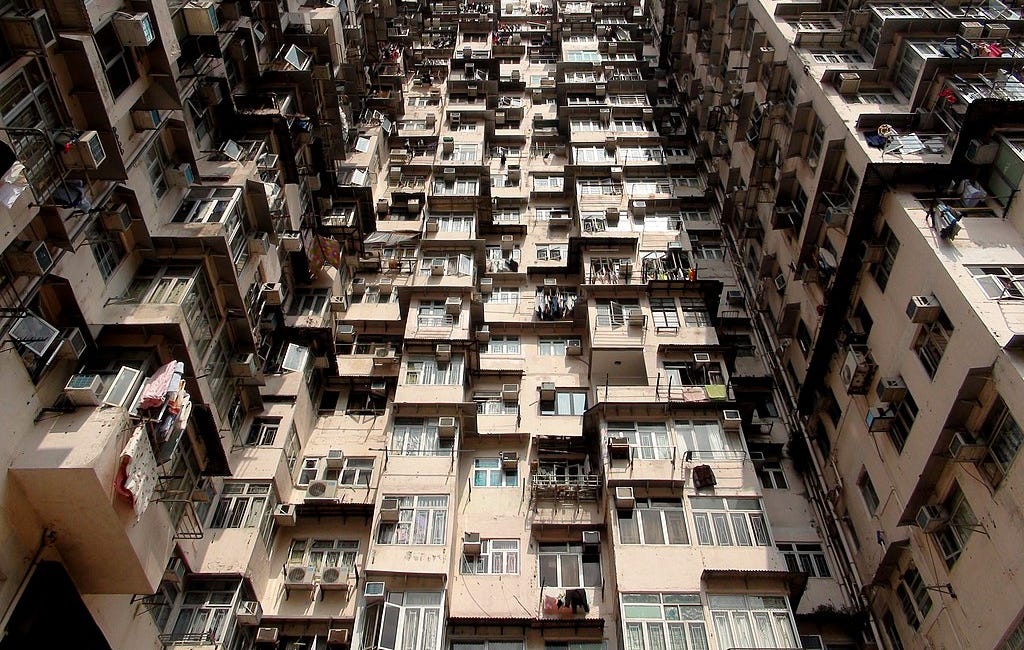

Early Years in Monster Building

1976. My mother, older brother and I moved in with Babba in the Quarry Bay area on Hong Kong Island. It was an enclave for new immi…

I will write about my humiliation with my second foreign language, English, in a future newsltter. Stay tuned.

Thank you for reading this essay and engaging with me. I appreciate your time and interest so very much.

Currently, my newsletter is free, as I don’t feel like charging a subscription fee when I can’t guarantee a regularity of publication at the moment. However, you are always welcome to buy me a cup of tea (or more)! Also, most of my essays in the archive (older than six months) are behind the pay wall. If you wish to read one, I’d appreciate a donation of a cup of tea for that privilege. Simply mention the title of the essay in your comment after clicking the button below, and I’ll send you a secret link. Make sure you set your comment to private. Thank you!

The Executive Order Designating English as the Official Language of The United States

A Trump order made English the official language of the U.S. What does that mean? by Vivian Ho and Rachel Pannett, The Washington Post. (Note: Thanks to a friend’s sharing, I got alerted for this development. Otherwise, the WAPO is a newspaper I’ve quit subscribing to due to its editorial stance.

The data comes from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey’s 2023: ACS 5-Year Estimates Data Profiles and its 2023 report “What Languages Do We Speak in the United States?

What a great article which I restacked. I know you well as a dear friend of many years and have always admired your polyglot abilities. This well researched and thoughtful article gave me even deeper perspective into your experience and that of other immigrants. I can now be a better ally. I find myself facing a new language barrier as I settle into life in Barcelona yet to begin my study of Spanish. I do not expect local Catalans to speak English; it is my responsibility to learn Spanish or Catalan. Of course I am grateful when they do have some ability to speak English (although I always try to use the Spanish phrase first). But I am thankful to live in a country that does offer free government run language classes for immigrants. I experienced this too as you did learning to speak Swedish when I lived in Sweden in 1989-2007 and agree how generous & supportive Sweden is to immigrant language learning). The third foreign country I lived in was Malta. As a former English colony well into the 70s, English has remained as an official language along with Maltese (and sadly the Maltese language has often taken second tier to English even by the natives). So it was perfectly possible to speak English there. I did admire those immigrants I knew who attempted to learn the difficult Maltese language. In short, multiculturalism and diversity of languages and backgrounds makes us better and stronger and more innovative nations and society. Infuriatingly, this current regime does not agree.

I admire you and those who are multilingual. It’s incredible how it broadens perspectives and enriches lives in ways I can’t experience. I regret that I've only mastered my native language. After I visited Italy, I went home and enrolled in classes, hoping to tap into my ancestral roots for better learning. However, balancing my job and studying proved challenging, and I long ago abandoned that aspiration.