Goldfish Uncle and Gentle Gweilo

6. A childhood sexual trauma that unknowingly shaped the relationships the rest of my life

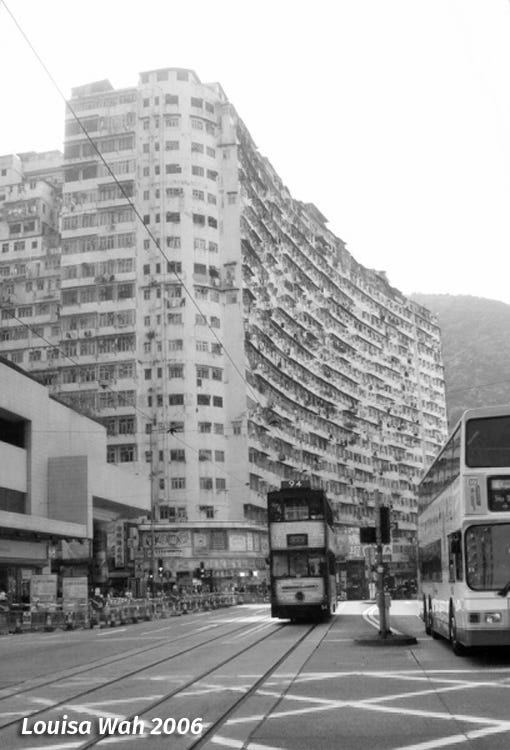

On a sweltering summer's day in 1983, I took the tram to school. I had been doing that since my mother decided that I was old enough to travel on my own a year earlier.

The tram was extremely crowded, as usual. A middle-aged man with bulging eyeballs, o…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Lily Pond to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.